My mum died on 15 March 2024. Here is what I wrote for my mum.

Mum’s mum, Tan Siu Eng, met the tall and strapping quantity surveyor, Yuan Chee Fong, known as Shanghai (because that was his hometown), and they married and started a family. Mum was born in Singapore on 22 January 1936 in the Year of the Pig, as Gek Neo. She was the middle child, with one older brother, Eng Kee and a younger brother, Eng Guan (later known as Robert). Although she was not the youngest, Mary was known as Sister Baby.

As a child, she liked to play with the kids down in the village, fighting spiders. She treated the family’s goose as a pet and refused to eat it when it was served up for dinner. Mum used to run to the village to put her mum’s lottery numbers on and would massage an old lady’s back in the village for a few coins. Her mum was the disciplinarian of the family, but Mum used to also tell stories of how kind her mum had been to strangers, buying up all the unsold buns from the peddlar, before Mum’s family lost everything in the war.

She grew up under Japanese occupation during WW2, and must have witnessed horrors and experienced significant deprivation.

Mum left school very early to help the family after her dad died, to help pay for her brothers’ education. She worked at a bookstore, then later at a pharmacy.

When she was about 21 years old, Mum left Singapore and moved to Penang, in Malaya, where her waters broke on the ferry from the island to the mainland and she gave birth to her first daughter, Deborah, in 1959. It was a Valentine’s Day when Mary married Leo, and Deborah was the youngest person aboard the plane when they moved back to Australia.

In Australia Mum’s family grew exponentially. She gave birth in quick succession in the 1960s to Theresa, Susan and Jenny. I can’t imagine what having four small children would have been like, for a Singaporean woman in her twenties, living on an Australian suburban army barracks, whilst her husband was often away.

They finally got their boy, David in 1969, who made the Bankstown newspaper born with two teeth. They bought their first house on Station Rd, Loganlea after Dad left the army, and then in the 1970s they had their lovely final surprises, Allison and Jackie. Allison was diagnosed with a brain tumour at the age of ten, and Mum was her primary carer for the next 30 years.

Dad used to drive the bus amongst other jobs to keep the family afloat, and he once tried to teach mum how to drive. Apparently Mum nearly drove the car into the river, which was the last time she ever sat behind a steering wheel, at least literally.

But in the figurative sense, Mum was always the driver of the family. She was the boss, often the tyrant. Occasionally she was a benevolent dictator, after a win on the horses.

I think I can say that all her children have memories of Mum’s anger. I don’t know if she realised the impact she had on us. I don’t think she realised that we would remember those words. Maybe she thought we would only hear her, or see her, if she shouted, or left actual marks.

Some of my happiest memories with mum are watching TV, even though she used to have at least two going at once, often with the radio as well, which I credit with my ability to concentrate. One time, when we were living at Station Rd, I remember her coming to get me out of bed so I could watch Goodbye, Mr Chipps with her, because she really liked that movie.

I remember watching the Australian Open with her every year in the summer holidays. Sometimes, in the evening in front of the TV, at the house in Slacks Creek, she would bring us each a bowl of ice-cream, Neapolitan flavour. I remember the smile on her face when she did that.

I do have side-eyed memories of mum’s tenderness. I remember one time, overhearing her telling Dad that she was worried about me swapping my university courses, whereas I had not even realised she had paid attention to what I was studying. She used to tell us of nightmares she had of one of us being kidnapped and sold across the Straits.

And she told strangers about all her children’s achievements, and later, also her grandchildren, carrying in her capacious handbag photos, certificates, articles about Allison, business cards, to show off.

Mum’s main love language was food. She would pile plates as high as she could. After Deborah moved out of home, I remember that the smell of Mum’s chicken curry meant Deborah was coming for a visit.

I’m not a psychologist, and I don’t want to gloss over the negatives. But I don’t think it was an easy journey for mum. She carried her own trauma. I think she loved Allison and all of us in the best way she could. When she got angry, maybe it was not us, or only us, whom she was angry at. Maybe the love she did give us was more than she had ever received.

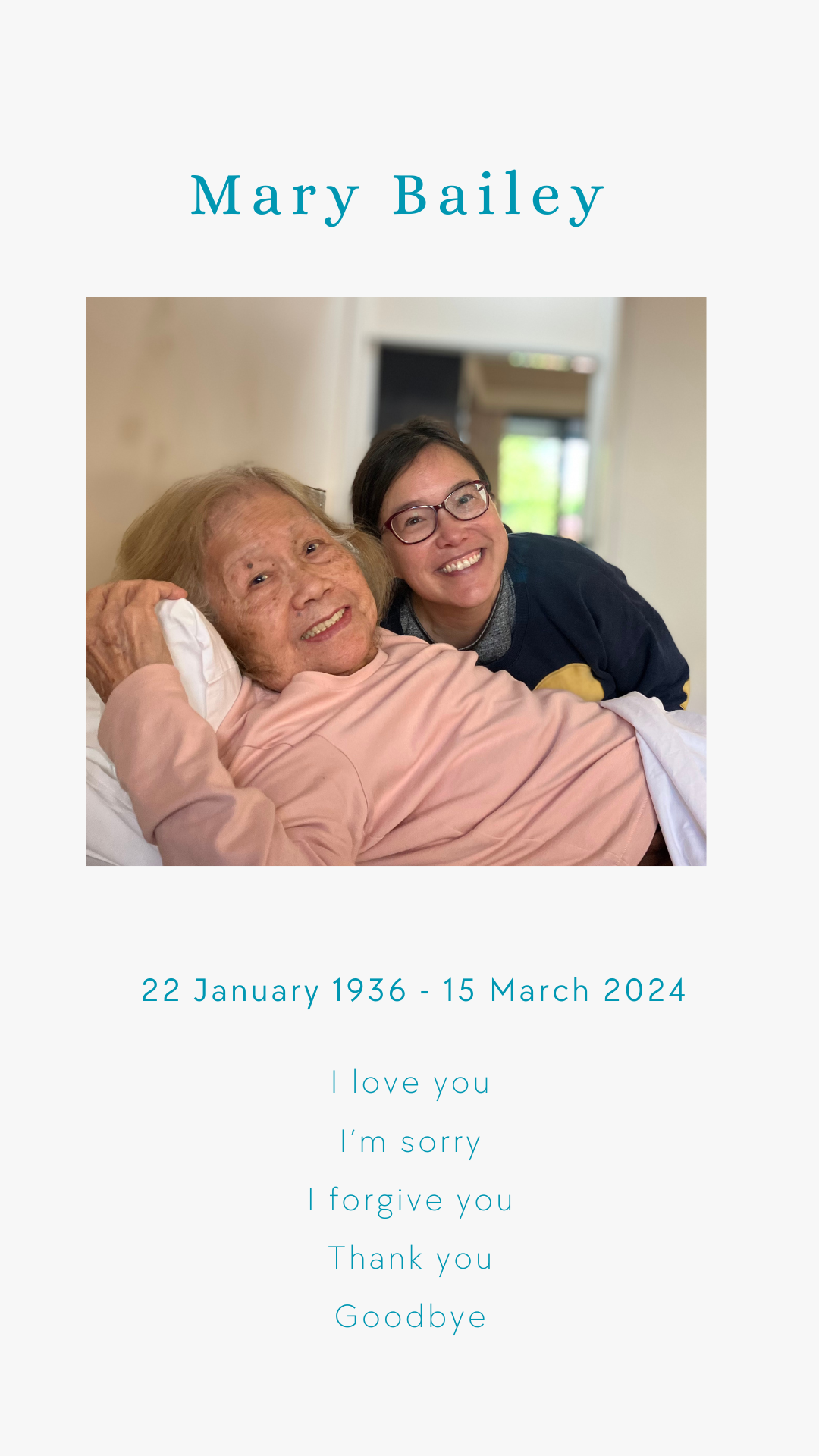

In the last few years, the dementia seemed to subtract the anger and leave the joy. On my last visit to Mum, at the aged care home, she tried to give me her biscuits, her lunch. After I refused these, she kept eyeing a glass of water on the table, intended for a resident who was not yet at the table, and kept offering it to me.

Mum. The grin on your face when one of us came to see you here at St Vincent’s. You let me kiss you on the cheek. I like to think the dementia let you say things you had never said before. Maybe you had thought them over the years.

Maybe you had not realised how much your love, how much you, might matter to us; how much your words might mean to us.

‘Good girl, nice girl, good daughter. Love you.’ I am grateful I heard these words from you.

Mum, I love you too. We forgive you. We love you. We’re sorry. Please forgive us. Thank you. Now lay down your burdens and be at peace. It’s time to go. Good-bye.

Contact me

Get in touch any time for a free, no-obligation quote and a chat about your needs.

0428 576 372

jackie bailey writes at gmail dot com